Three Lessons from the International AI Safety Report for the Independent, International Scientific Panel on AI

-

Event

-

AI Governance

-

Multilateralism

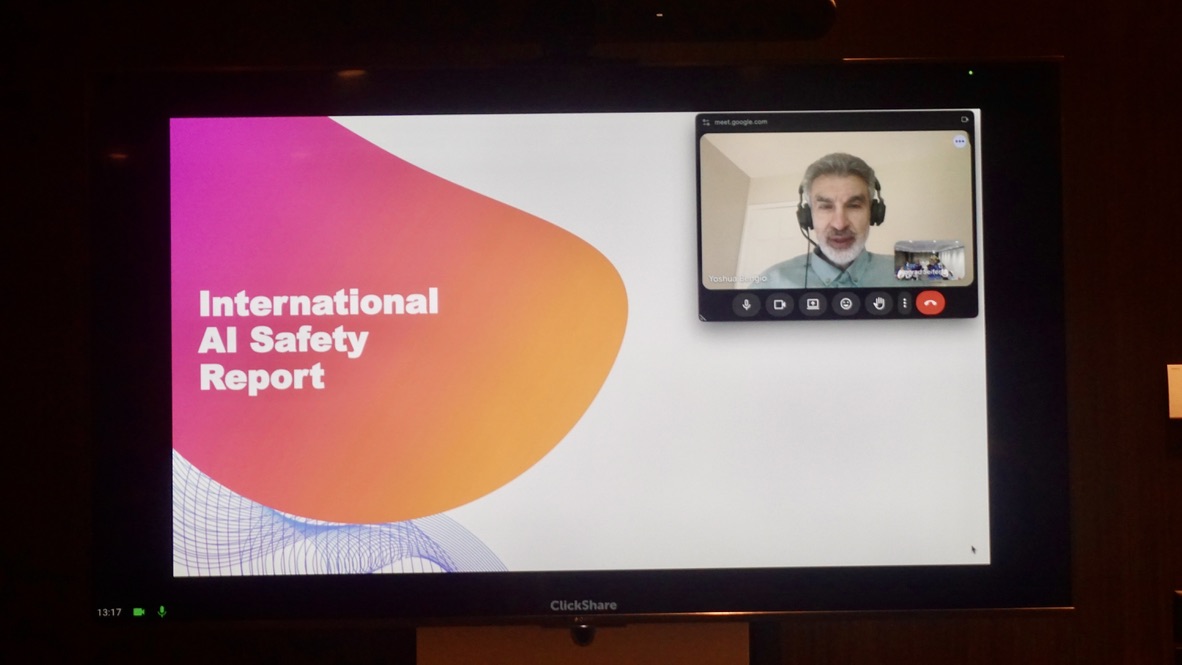

On the margins of the 2025 AI for Good Summit, the Simon Institute for Longterm Governance (SI) organized an event on the International AI Safety Report and what lessons we can draw from it for the implementation of the Independent, International Scientific Panel on AI that is currently being negotiated at the UN. The event featured contributions from Prof. Yoshua Bengio (chair of the report), Dr. Sören Mindermann (scientific lead of the report), and Hannah Merchant (Report Secretariat, UK AI Security Institute).

The International AI Safety Report was one of the outcomes of the AI Safety Summit in Bletchley in November 2023. It was written by over 100 international AI experts and supported by 33 countries and international organisations. An interim report was published in May 2024, and the first comprehensive report followed in January 2025.

The following were some of the key lessons discussed at our event:

a) We need both trusted senior experts broad expertise and more junior specialists on specific topics

There are a limited number of top AI experts, and they are in very high demand. To ensure that a panel has scientific and political credibility, it needs trusted senior experts that can guide the overall scientific work. At the same time, on many subtopics, there are only a handful of experts in the world (who are sometimes younger and not as credentialed), and there needs to be freedom to engage these experts to draft substantive content.

b) Reviews present opportunities for countries, industry, and civil society to be heard

Inclusivity is important and the review stage is a good place to strengthen representation and legitimacy without compromising scientific independence. The International AI Safety Report considered more than 1,100 lines of feedback from its Expert Advisory Panel with country nominated experts, as well as its industry and civil society reviewers.

Whereas the International AI Safety Report focuses on a selected group of countries, the Independent, International Scientific Panel on AI is expected to be open to all UN member states. This means experts from across a wider grouping would have an opportunity to engage with its findings and provide feedback. At the same time, this engagement should not undermine scientific integrity.

c) Scientific synthesis is an important step, but we cannot expect it fully resolve the evidence dilemma for policymakers

The evidence dilemma in AI highlights a tough reality: policymakers often must make decisions before strong evidence is available, and there is a risk that early actions based on limited evidence can be insufficient, ineffective, or unnecessary. This echoes the Collingridge dilemma, which says it’s easier to shape technology early, but harder to understand its full impact until later. Efforts like the International AI Safety Report and the Independent International Scientific Panel on AI are crucial for strengthening the evidence base. However, even with the best science, we won’t eliminate decision-making under uncertainty.

In some cases, demands for perfect evidence can also be an intentional tactic to delay action. By the time we have very robust evidence of long-term effects based on large scale double-blind randomized control trials, it will probably be too late to respond to an AI issue effectively.

Societal preparedness under uncertainty

The discussion amongst participants highlighted that it remains difficult to make AI capabilities forecasts beyond 2030, let alone as far as in domains like climate change with targets for 2100. However, the next version of the Report could include the development of multiple reference scenarios as one relevant way to deal with the scientific uncertainty around the timelines of future AI capabilities. More broadly, the discussion highlighted that a purely reactive approach is not sufficient, and that policymakers should have a proactive mindset in preparing societal risk management for a range of scenarios.

Yoshua Bengio, joining the event remotely to provide an overview of the process to develop the International AI Safety Report. Photo credits: Simon Institute.